In the last week the “First International Congress on Comunalidad” about communal struggles and strategies has taken place in Puebla, México. It was a plural space with the aim of engaging in rigorous and profound discussions on economic, social and political issues related to the horizons opened through community-popular struggles. This debates on comunalidad, communalism, and struggles for the commons have proven their relevance for the understanding of new social and political problems in moments of crises of capitalism.

In the last week the “First International Congress on Comunalidad” about communal struggles and strategies has taken place in Puebla, México. It was a plural space with the aim of engaging in rigorous and profound discussions on economic, social and political issues related to the horizons opened through community-popular struggles. This debates on comunalidad, communalism, and struggles for the commons have proven their relevance for the understanding of new social and political problems in moments of crises of capitalism.

Hereafter summary of the article about oaxacan comunalidad by the zapotec anthropologist Jaime Martínez Luna, who took part in the Congress:

The history of Oaxaca has been interwoven with principles and values that display its deeply rooted comunalidad. For the Oaxacan people across many centuries, this has meant integrating a process of cultural, economic, and political resistance of great importance. Since the Spanish conquest individualist and mercantilist as it was Oaxaca has responded with a form and reason for being communal that has permitted it to survive even in the face of an globalizing process. The concept of comunalidad, can be seen as the central concept in Oaxacan life.

The existence of a polytheism which sacralizes the natural world, the absence of private property, an economy oriented toward immediate satisfaction, and a political system supported by knowledge and work, led the original peoples to create a cosmovision originating from the us, from the self-determining and action-oriented collective, and, along with this, to construct a communalist attitude which has been continually consolidating itself despite cultural and economic pressures from outside.

COMUNALIDAD AXIS OF OAXACAN THOUGHT

In Oaxaca, the vitality of comunalidad as it presents itself witnesses to the integration of four basic elements: territory, governance, labor, and enjoyment (fiesta). The principles and values that articulate these elements are respect and reciprocity. Comunalidad and individualism overlap in Oaxacan thought. Everyone displays knowledge according to the context surrounding them; hence, contradictions are a daily occurrence, not only of individuals, but also of communities.

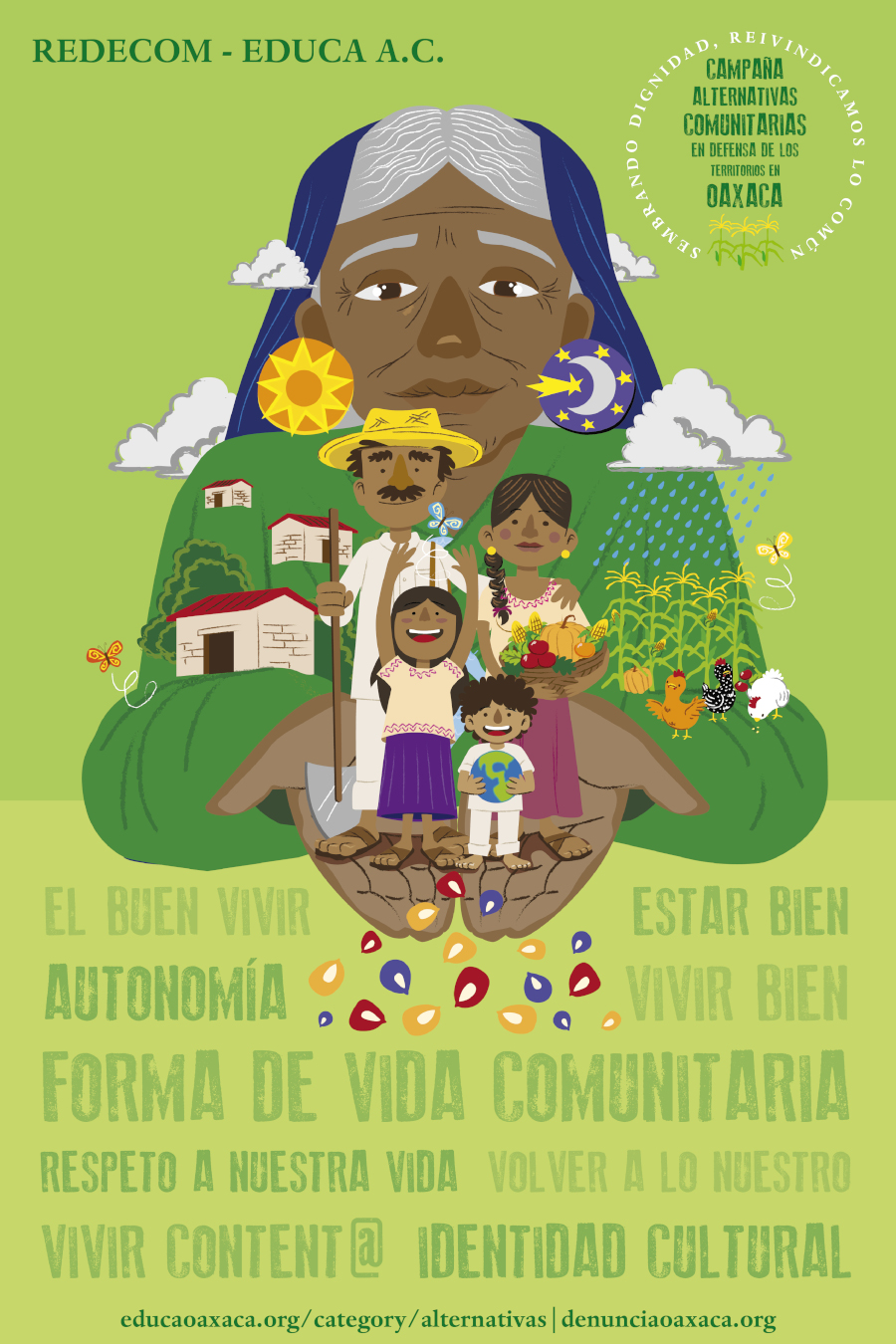

Communal beings make sense of themselves in terms of their relationship with the land. An indigenous person understands himself in relationship with the land. It is a relationship of sharing and caring. That is, humans are linked to the land not only for organic sustenance, but also for spiritual and symbolic sustenance. In other words, the land does not belong to those who work it – rather – those who care for it, share it, and when necessary work it belong to the land, and not the other way around.

Obviously in a world ruled by the logic of the market, it is easier to appropriate everything from nature for ourselves rather than to grasp an entirely reverse conception of ourselves. Comunalidad is a way of understanding life as being permeated with spirituality, symbolism, and a greater integration with nature. It is one way of understanding that human beings are not the center, but simply a part of this great natural world. It is here that we can distinguish the enormous difference between Western and indigenous thought. The market makes everything into a product, a thing, and with that nature is also commodified.

The second reflection is on organization. This necessary organization is obligatory, not only for peaceful coexistence, but also for the defense of territorial, spiritual, symbolic,

artistic, and intellectual values. The community is like a virtual gigantic family. Its organization stems initially and always from respect.

The creation and functioning of the communal assembly perhaps was not necessary before the arrival of the Spaniards, but for the sake of defense it had to be developed. Once the population was concentrated, religious societies to attend the saints (cofradías), and community organizations to plan fiestas (mayordomías) developed, which were cells of social organization that strengthened the ethics of the assembly. Out of this, the communally appointed leadership roles (cargos) originated. Someone had to represent the group, but all this implied the need for greater consolidation for decision-making.

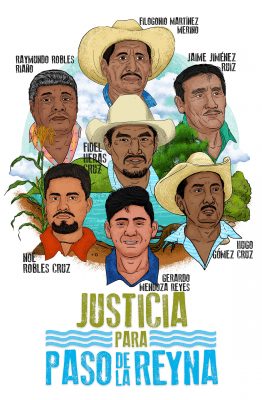

Today, as before, one does not receive a community cargo by empty talk, but rather because of ones labor, attitude, and respect for the responsibilities entrusted. Everyone knows this, having learned it even before the age of eighteen, perhaps at ten or fourteen years of age, when assigned the first cargo, that of community policeman (topilillo). This gives the cargo a profound moral value that has nothing to do with categories such as economic value, efficiency, profitability, or punctuality, but rather with respect for the responsibilities involved. This has created a truly complicated political spectrum in Oaxaca, including 570 municipalities and more than 10,000 communities. Eighty percent of these continue to govern themselves by communal assemblies. Their representatives are named in the assembly. For this reason, the widespread civic uprising that occurred in 2006 in Oaxaca must be analyzed under more meticulous parameters, a topic that will not be addressed here.

The third reflection refers to communal work. To begin with, communal labor does not respond to the drive for personal satisfaction, that is to say, it does not obey the logic of individual survival, but rather that of satisfying common needs, such as preparing a plot of land, repairing or building a road, constructing a community service hall, hospital, school, etc. This labor is voluntary, which implies that individual wages are not received. In the urban world, everything is money-driven; you pay your taxes and away you go.

Another reflection concerns the fiesta. In a neoliberal context, it is the market that establishes the rules, and it demands greater production of merchandise. In the community there is production, but it is for the fiesta. All year long every nuclear community cultivates its products: corn, beans, squash, fruit, chickens, pigs, turkeys, even cattle. For what? For the fiesta. Here is the root of the difference. The community member does not work to sell, but for the joy derived.

Read more about Comunalidad:

Full article by Jaime Martínez Luna: Comunalidad as the Axis of Oaxacan Thought in Mexico

Blog (SPA) Jaime Martinez Luna

First International Congress on Comunalidad (October 26, 27, 28 and 29, 2015)

Twitter: Congreso Comunalidad 2015

![]()